Ralph Ingersoll was the son of an engineer. After graduating from Hotchkiss prep school he was accepted to Yale University where he earned an engineering degree. From there, he spent a year working in a mine in Mexico before moving to Brooklyn, New York to live with Lillian Hellman where he wrote about his experiences in Mexico.

The move was his way of getting out from under his father’s control so he could pursue his true passion, journalism. He became the managing editor of The New Yorker, publisher for Fortune and general manager of Time, Inc. He founded PM, a tabloid magazine. As a journalist, his stories polarized readers. Ingersoll had a reputation as a creative thinker, but many said he was a liar that would say anything to get what he wanted. The one thing he couldn’t talk his way out of was a draft summons.

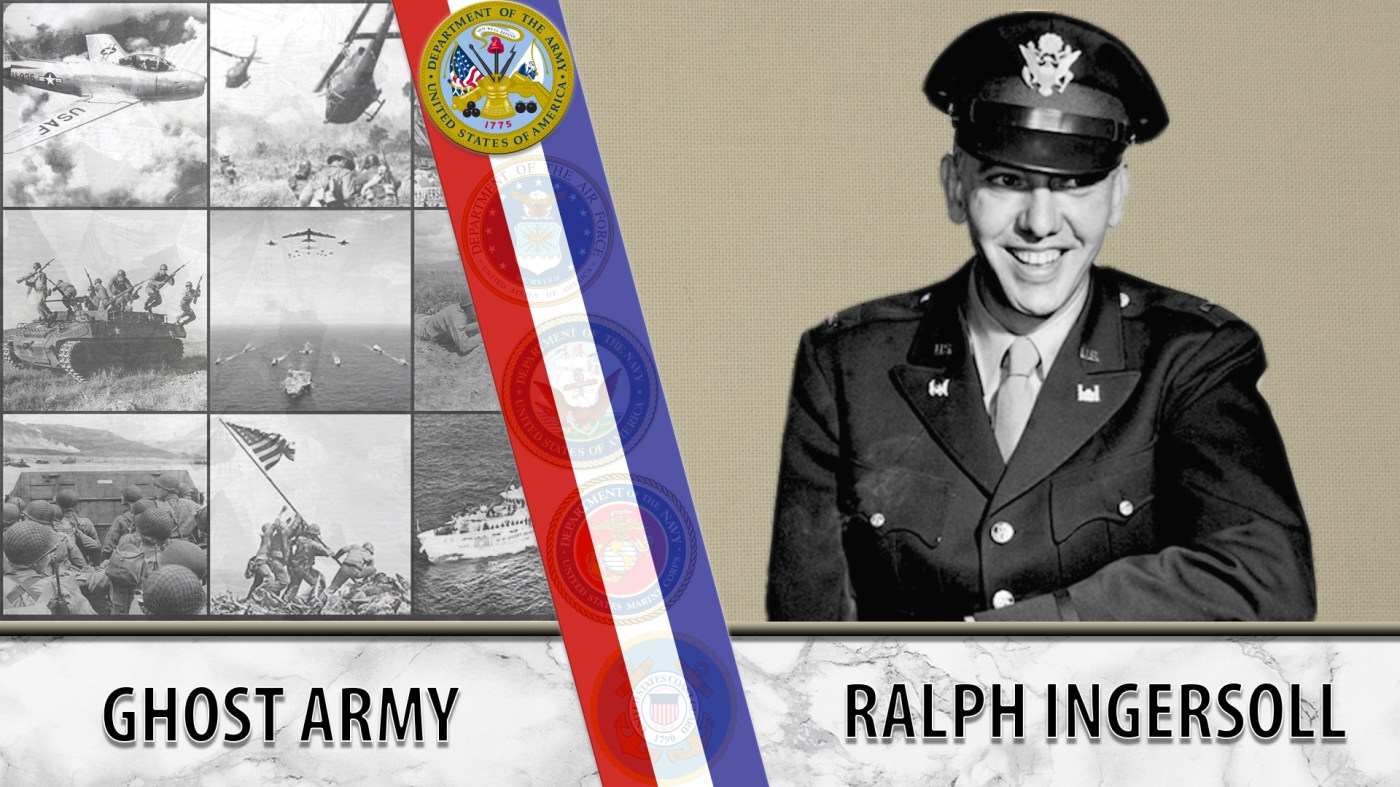

Ingersoll enlisted as an engineer and went to basic training in Cape Cod. He was chosen to be part of a general’s staff and was soon commissioned as an officer. From there, he moved up the ranks to colonel. While living in London during the early days of World War II, he conceived the idea for a phantom army. He wrote up a report and sent his idea Washington. Shortly after, the United States began assigning people to make Ingersoll’s idea a reality. However, they didn’t choose personnel from the draft. The directors of the program actively recruited artists, architects, set designers and actors from Philadelphia and New York City art schools.

The Ghost Army had camouflage, sonic and radio. The camouflage unit was equipped with inflatable tanks, cannons, jeeps, trucks and airplanes. The sonic unit used state-of-the-art recordings of mobilization that could be broadcasted up to 15 miles. The radio unit was part of Signal Company. They created spoof traffic nets and impersonated radio operators from real units. There was never more than 1,100 men assigned to the Ghost Army, but they were about to fool the German’s into thinking a ten man outfit was a ten thousand man unit. In 1944, the Ghost Army proved useful to Gen. George Patton when they held a dangerously undermanned part of Patton’s line at the Battle of Metz, impersonating an infantry division until the real division arrived. In all, they’re credited with saving an estimated 25,000 lives with their deceptions.

What began as an epic idea in Ingersoll’s imagination helped win World War II. Today, we honor Ingersoll for his ingenuity and creativity in helping form an invaluable unit that helped the United States.

We honor your service.

Topics in this story

More Stories

Army Veteran Malika Montgomery says one of the things that helped her live her best life with multiple sclerosis was surrounding herself with positive people.

Acknowledging the issues that Veterans face and working toward solutions is crucial for ensuring they have the support they need to thrive in civilian life.

Last year, Move United hosted 26 adaptive sports competitions in 22 states for 1,537 individual athletes. This year, that number is increasing to 35 events in 24 states for even more Veteran athletes.

Thank you, Alisa. Have read a few times about Ghost Army, including Wikipedia, but this is the first time see Ingersoll’s contribution.