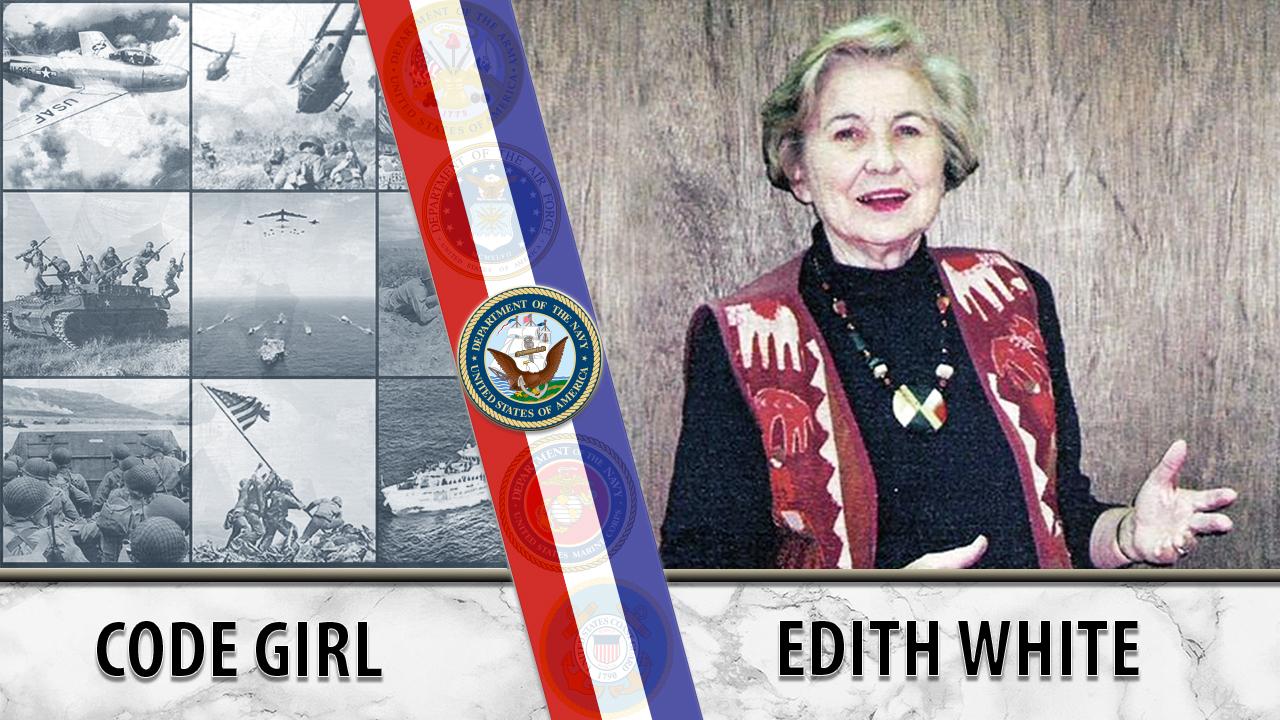

Edith White was World War II’s “Code Girl,” working as a shift commander with the Navy WAVES unit to crack Japanese codes in the Pacific.

Edith Reynolds White was born in Passaic, New Jersey, in 1923. Growing up, she attended a small private school where there was “good literature, good foreign language… a marvelous education in depth,” but one that lacked any real teaching in science.*

White had always valued education. When her father passed away, many of White’s relatives suggested she stay home and care for her mother. However, White had other ideas. She skipped two grades and received a scholarship to Vassar College at 16.

Working her way through school, White sent money back home to her family. She ran the student self-help bureau and worked for college shops during the summers. While White attended college, the United States entered World War II. “Many of my best friends were being killed,” she said. When a Navy captain visited her campus and summoned those with the necessary math and language skills to use in Naval Intelligence, she felt compelled to sign up to save her country.

White began taking secret courses in code-breaking and cryptography. When she graduated from college at 20, the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) commissioned her. The WAVES unit worked to crack Japanese codes and earned commendations twice for breaking codes that eventually led to American victories in the South Pacific. White served as a shift commander in the unit.

After her service in the WAVES unit, White went to work in a tuberculosis hospital in New York. At the time, a cure for tuberculosis had yet to be developed and many young men were returning home with active TB contracted from the South Pacific. White assisted the patients with job and college training along with post-recovery life planning.

At the TB hospital, she met Dr. Forrest White, who was finishing his medical internship. Edith was to receive a unit citation for breaking Japanese codes. The hospital never had WAVES officers before and decided to hold a ceremony to decorate them. For the occasion, Edith needed to borrow someone’s ribbons: she borrowed those of Dr. Forrest White, and the two married that following fall, 1946.

The Whites had two children, Hap and Holly. They moved back to Dr. Forrest White’s hometown of Norfolk, Virginia. The family found the first year of transition tough because Forrest suffered from polio. Meanwhile, Edith was occupied by the campaign for Francis Pickens Miller for the U.S. Senate. When Forrest recovered from polio, the two spent a lot of time rebuilding his strength by playing tennis together.

Edith was enthusiastic about civil rights and worked to bridge the racial gap between black and white communities as a member of the Women’s Interracial Council. She began fighting for better facilities at Booker T. Washington High School, which was for black students only. Together, the White family helped found and lead the Norfolk Committee for Public Schools, which was against Virginia’s Massive Resistance, a movement to block desegregation. The committee won a lawsuit that resulted in the desegregation of six Norfolk schools.

Edith’s work spurred hatred from their neighbors and friends. Many women stopped playing tennis with her. Burning crosses began appearing on their doorstep, and the family received many threatening phone calls. However, she did not give up. Instead, she kept fighting for racial equality and women’s rights. White played an instrumental role in organizing the League of Women Voters in Norfolk and actively encouraged women to register and vote independently.

In addition to her activism, White loved art and literature. She served as the first female board member of the Virginia Symphony Orchestra. She also endowed Old Dominion University’s Literary Festival, was an avid watercolor painter, wrote book reviews for The Virginian-Pilot, traveled to local schools as a storyteller, and was an active member of the Larchmont United Methodist Church.

Edith’s family never knew of her secret military service until a limousine arrived outside her son’s house in Norfolk’s Algonquin Park neighborhood in Virginia. A naval officer stepped out looking for Lt. Reynolds, a name which her son only then realized was his mom’s. Edith met up with the officer and they reminisced about the last time they spoke, which was during the war. Particularly, they recalled when he had traveled to Washington with a soaked Japanese codebook that was rescued from a sinking submarine, and Edith, alongside the other WAVES officers, strung the book on a clothesline and cracked the code. Her efforts contributed to the Battles of Leyte Gulf and the Philippine Sea.

Edith White died on June 6, 2020 from surgical complications in Williamsburg, Virginia. She was 96. We honor her service.

*From an oral history interview held in Old Dominion University Libraries Digital Collections. White, E., 1982. Oral History Interview With Edith White.

Writers: Calvin Wong, Aubrey Hutson

Editor: Ryan Pan

Fact Checkers: Samantha Knapp, Raphael Romea

Graphics: Brandi Muñoz

Topics in this story

More Stories

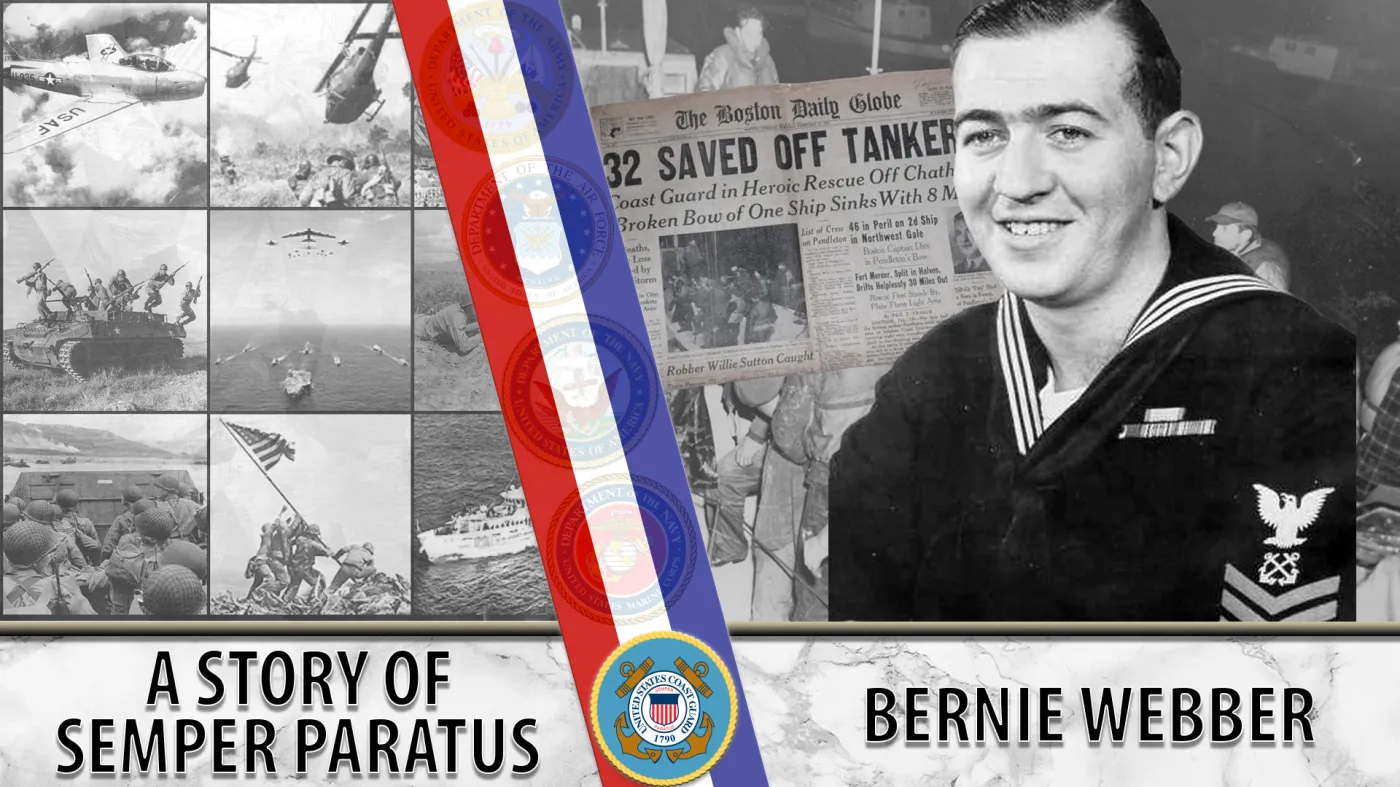

Bernie Webber led one of the greatest Coast Guard rescues in history that was later chronicled in the book and movie, “The Finest Hours.”

As the events of 9/11 unfolded, Marine Veteran Robert Darling served as a liaison between the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney in the underground bunker at the White House.

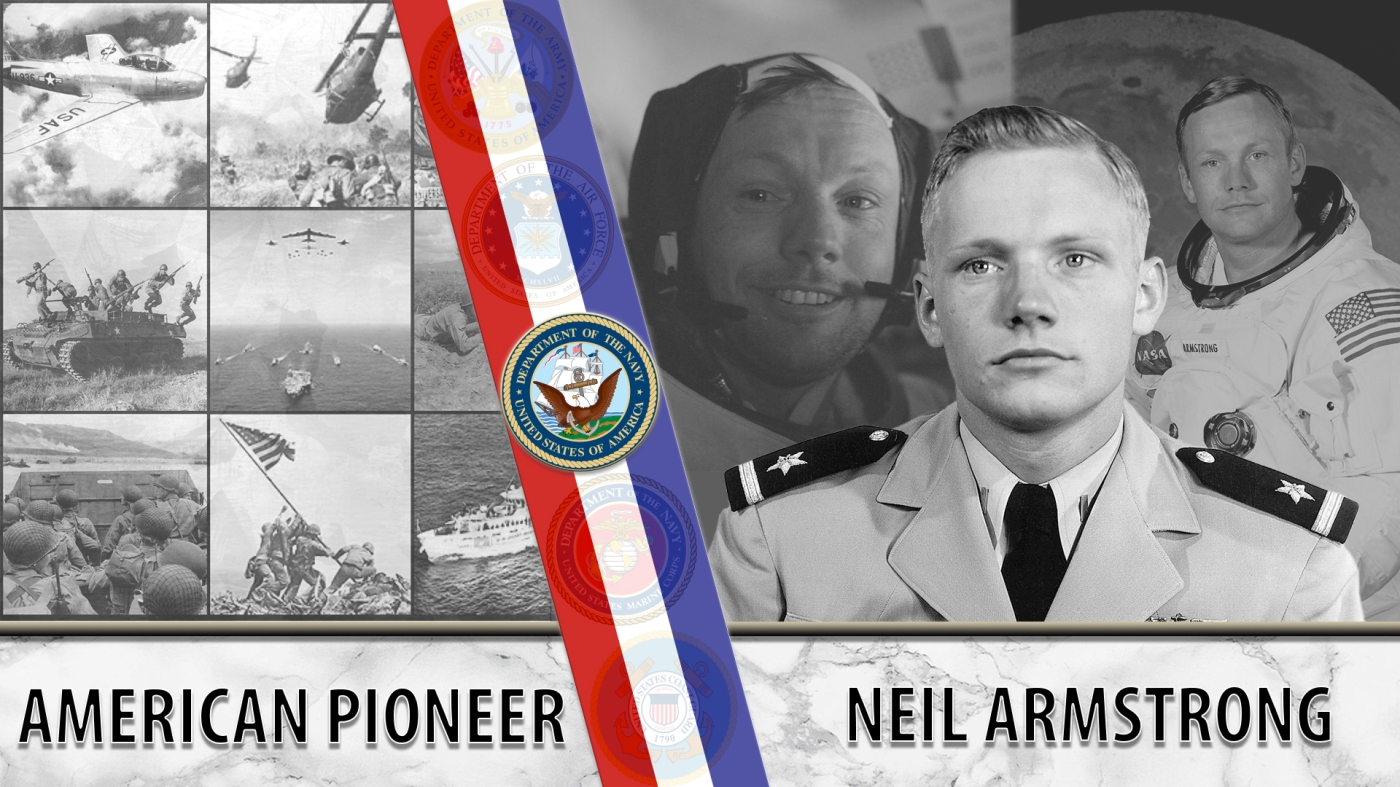

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon. He was also a seasoned Naval aviator.